‘I want Castlecrag to be built so that each individual can feel the whole landscape is his. No fences, no boundaries, no red roofs to spoil the Australian landscape: these are some of the features that will distinguish Castlecrag.’

‘With us here this widest phase of the architect’s work, landscape architecture, is unknown except as a meaningless name. Were the architect a factor in life today, this field would surely supply the motif for all his works, and our creations would be designed to serve natural need instead of artificial prejudice.’ (Griffin, 1922, AHB)

Griffin interviewed spoke of internal reserves as ‘…favourite playgrounds. Here all the children from the different houses can play together, where their mothers can see them, and where they are safe from the motor traffic in the streets.’

Landscape training and dual career focus

The Griffins are less known in America and even Australia as practitioners of landscape architecture than as architects, despite the number and scale of their landscape works.

Inspired by the park designs by Frederick Law Olmsted (often called the founder of American landscape architecture) of New York’s Central Park and his ‘green necklace’ of parks in Boston, landscape design was the career Walter Burley Griffin would have pursued had the opportunity offered. He had approached Chicago landscape gardener Ossian Cole Simonds for career advice before entering the University of Illinois in 1895. Apparently unsatisfied with the lack of relevant curriculum, Simonds urged him to pursue architecture and study landscape gardening on his own, as he himself had done. Griffin took what classes he could and, like Simonds and landscape gardener Jens Jensen, shared an approach to landscape design through architecture, an interest in civic design, urbanism and planning.

In 1902 there were only six ‘landscape gardeners’ (and no landscape architects) listed in the Lakeside Annual Directory of the City of Chicago (Chicago Directory, Chicago, 1902 pp2435–47). In 1912 only two landscape architects and 13 landscape gardeners were listed (i bid 1912 pp1552 & 1693).

Griffin was an avid naturalist. From 1908 he, Jensen and others, under the auspices of the Playground Association of Chicago (and later the Prairie Club), had led Chicago people on hikes through the remnants of rapidly vanishing native landscape to stimulate interest in its conservation. This was part of a nationwide movement of ‘Progressives’.

Griffin’s practice as a landscape architect was first featured in a public text in Wilhelm Miller’s The Prairie Spirit in Landscape Gardening (1915), which included Griffin as an exponent (along with Jensen, Simonds and architect Frank Lloyd Wright) of his proposed American regional ‘Prairie’ style. Simonds, Griffin and Miller had all attended the first national meeting of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 1913 in Chicago.

Miller cited ‘conservation of native scenery’ as his first principle (Miller, op. cit):

‘The Prairie Style is characterised by preservation of typical Western scenery, by restoration of local colour (native plants), and by repetition of the horizontal line of land and sky which is the strongest feature of Prairie scenery.’

Griffin did not share Miller’s and Jensen’s pronounced advocacy of native plants nor use motifs such as Jensen’s miniaturised rivers. He used exotic and cultivated plants as well as natives, and his designs fused natural and formal elements. Marion Mahony noted that Walter Griffin had used a high percentage of native plants as early as 1906.

By 1914 Griffin and his architect wife Marion Mahony had moved to Australia after winning the 1912 international design competition for Canberra with a scheme based on its topography, a distinctly non-prairie valley landscape of undulating hills.

Walter Griffin’s design approaches to landscape and architecture informed one another. Landscape itself, for example, crucially served as a basis for architecture — a conviction first made explicit in the Canberra publicity, Griffin noting (in Chicago) that: ‘…a building should ideally be “the logical outgrowth of the environment in which [it is] located”.’ In Australia, he hoped to ‘evolve an indigenous type, one similarly derived from and adapted to local climate, climate and topography.’

Marion Mahony Griffin and Walter Burley Griffin gardening in the backyard of “Pholiota”, Heidelberg, Victoria. National Library of Australia PIC P490/7

Rock Crest-Rock Glen Community and Landscape Plan, Mason City, USA. Photographer Mati Maldre, Chicago, Illinois, 1989

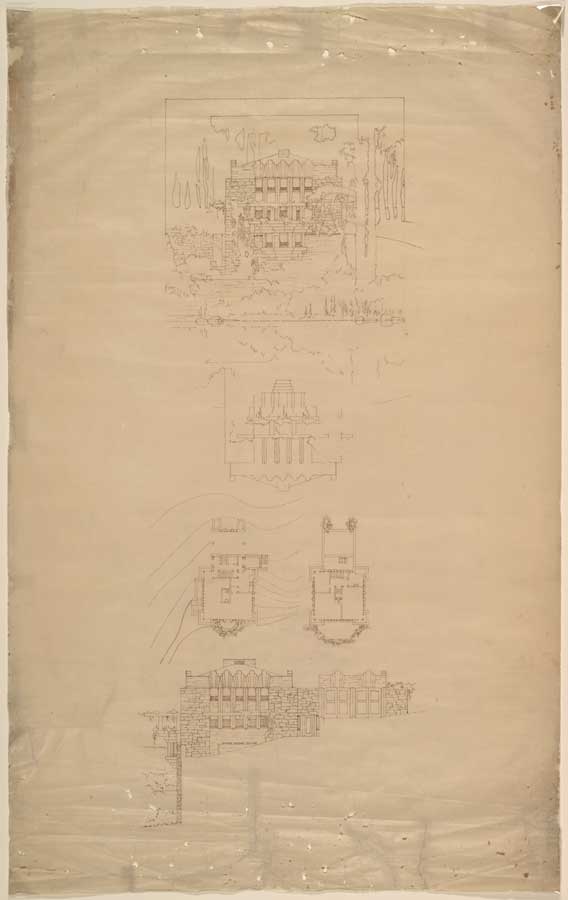

Detail from Joshua G. Melson residence, Rock Crest, Mason City, Iowa , 1912. Black ink over pencil on buff paper. National Library of Australia PIC/7456

A Canberra-led landscape architecture practice

The Canberra publicity shifted public attention from Walter Griffin’s architecture to his landscape architecture. Before Canberra his work had been limited in scope, and he had only designed one town plan, having primarily worked on domestic scale garden design, for example in collaboration with Frank Lloyd Wright (1901–1906; 1909–1911).

By the end of 1912 he was busy designing six communities in Chicago and distant Louisiana and Texas (Vernon, in Watson 1998; and in Turnbull 1998). A number of his residential projects capitalised on site topography, eg the 1912 Rock Crest-Rock Glen layout in Mason City, Iowa, where an 18- acre former quarry site straddling a stream was reused, retaining trees and creating internal reserves by covenants on title to prohibit buildings at the rear of each lot. The combination of architecture and landscape as complementary disciplines directed towards the creation of a coherent scheme for community living was a significant landmark in his career (Harrison, p.23).

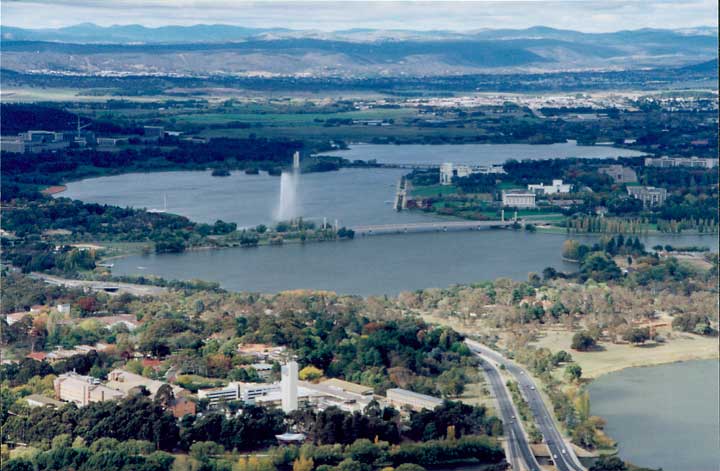

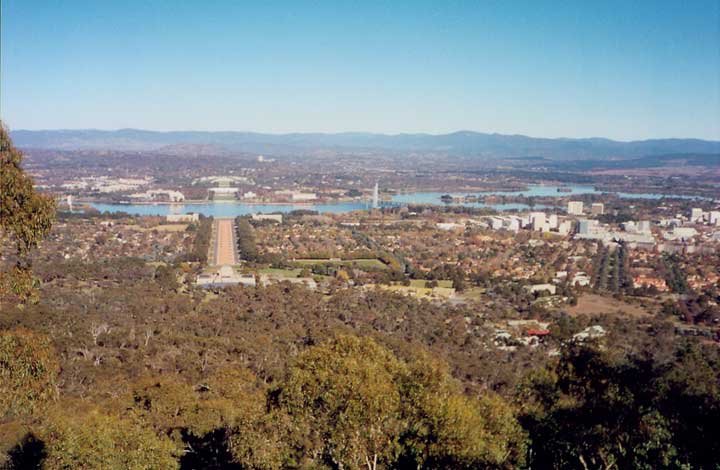

The Griffins’ Canberra entry placed Capital Hill at the centre of the city, as the nation’s physical and symbolic centre. Wide tree-lined avenues radiated from it towards all state capital cities. The plan was distinctive in how its structure and geometry sensitively related to the natural terrain of the site. A land and a water axis linked key elements Mount Ainslie and Capital Hill. A water axis linked Black Mountain and a series of lake basins to its east. A third municipal axis ran parallel to it from City Hill to Russell Hill. Lines through these points formed a great triangle at the city’s heart. With few exceptions avenues led the view to the skyline of hills and ridges which were kept free from development so that the natural valley setting took predominance over the city in its shelter (NCA 2005; Harrison 2001).

In Canberra’s suburbs Griffin included potential for developing larger residential blocks in a variety of schemes including ‘commons gardens’ and perimeter-block housing, leaving the block centres free for shared open space. After this the scale of the Griffins work gradually increased to whole suburbs and towns.

In Australia, as well as ‘Canberra’ work, Griffin designed innovative suburban residential subdivision estates starting with Mount Eagle (1914) and Glenard (1916) in Heidelberg, Melbourne. Both featured curving streets following topography and allowing enjoyment of views (and appreciation of the landscape), with internal block reserves at the rear where children could safely play, controls on the size and type of houses and materials.

By 1915, still working on some American projects, Griffin had designed campuses for three American universities. This was in addition to his inclusion of the Australian National University site in his Canberra plan, schemes for the University of Sydney, Melbourne’s Newman College and a competitive design for the University of Western Australia.

Quoted in 1922 Griffin promoted regard for environment (AHB, 11/1922):

‘The relation of the larger architectural efforts of Asia and ancient Africa and America, as well as the African cities, is that of a beautiful part of Nature’s magnificence, in which the more artificial graduate to the most unrestricted Nature without incongruity. With us here this widest phase of the architect’s work, landscape architecture, is unknown except as a meaningless name. Were the architect a factor in life today, this field would surely supply the motif for all his works, and our creations would be designed to serve natural need instead of artificial prejudice. The scope, scale, materials, proportions and the details of embellishments of a building are naturally only functions of the group with which it must fit, and that, again, of the larger landscape…

Internal reserves, pedestrian paths: contact with nature

Internal reserves were part and parcel of the Griffins’ ‘land planning’ and idealism for remaking surburbia and, indeed, society. They imagined uses like childrens’ playgrounds, social centres, nature reserves and links with an intricate system of pedestrian ways calculated to bind communities together, physically and socially.

Interviewed in Melbourne in 1913, Griffin spoke of internal reserves as

‘…favourite playgrounds. Here all the children from the different houses can play together, where their mothers can see them, and where they are safe from the motor traffic in the streets.’

While the Griffins did not invent the internal reserve, nor introduce it to Australia, they were both ardent proponents of the idea in early twentieth century residential planning in Australia. Covenants on land surrounding reserves gave residents a part-share, an interest in maintaining them. All of their ten Australian suburban estate plans (in Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra) and rural townships (Griffith, Leeton and Jervis Bay) included them, and they continued to promote them beyond the time when most other designers had abandoned them as impractical, wasteful and difficult to maintain.

Castlecrag: a landscape-based community?

After severing the link with Canberra the Griffins focused on the Castlecrag and Haven estates (from 1921), their one subdivision exercise in Sydney. This was their most substantial ‘model suburb’ planning work in Australia, a vehicle for their diverse talents and a model to try to remake Australian society.

Both were active public advocates for the estate, giving talks, writing in magazines etc, perhaps influencing others more widely than the rather limited actual land sales and initial owners moving in. Walter Griffin asserted that better environments with increased numbers of lots, together with community open space, could be created by careful planning that respected the landscape character of the site itself.

Griffin stated:

‘I want Castlecrag to be built so that each individual can feel the whole landscape is his. No fences, no boundaries, no red roofs to spoil the Australian landscape: these are some of the features that will distinguish Castlecrag.’

Castlecrag went further than previous projects. The plan was a garden suburb in a forest setting responding to the site’s topography, nature and views. Small lots with small houses were planned along narrow streets following contours; rock outcrops, creek lines, mature trees and remnant vegetation were retained in a system of internal reserves, many on plateau-top sites with long views; a foreshore reserve open to all ran along the water; and a system of pedestrian paths with no fences linked all to it, nature and each other.

The pedestrian path network ‘behind’ blocks also provided easements for services such as power lines and sewerage, keeping these and their periodic upgrading off public streets and from detracting from the predominant vegetated streetscape.

At intersections and the ends of cul-de-sacs, land not needed for vehicles was retained as ‘islands’ or remnants of original bush cover or natural rock, something unique. The Griffins saved seeds from local species and propagated them to revegetate the degraded plateau of Castlecrag which had long been affected by commercial firewood clearing. Until 1940 all Castlecrag residents were required to pay a levy for internal reserve maintenance and many participated in working bees (Walker, in Turnbull and Navaretti 1998).

An increasing love and use of Australian plants in landscaping

The Griffins immersed themselves in social circles allowing them to bushwalk in landscapes in Melbourne, Canberra and Tasmania, getting to know native soils, plants, communities, and growing requirements. Marion Mahony prepared extensive lists in books grouping native plants by seasonal flower colour, for use in Walter Griffin’s ‘colour-specific’ landscape schemes. Plans for revegetating Canberra’s then degraded hills such as Mugga Mugga, Red Hill, Black Mountain and Mount Ainslie aimed to ‘paint’ the hills in single colour vegetation assemblages in the process of revegetation, using wattles, bottlebrushes etc.

Marion Mahony was increasingly involved in landscape work. She wrote in 1916: ‘ At present I am doing mostly listing of native plants for planting now for both private work and the F C’ [Federal Capital]. (Rubbo, in Turnbull and Navaretti 1998)

As noted above, the Griffins did not exclusively use natives, also favouring the odd dramatic exotic plant such as a Bougainvillea draped over a pergola, Wisteria etc. However care was taken to make gardens ‘fit’ with, or complement, their natural setting rather than shout their difference. Marion Mahony’s beautiful series of ‘forest portraits’ (28 tree studies in pen and ink and wash) records the diversity of forest types, the unique beauty and form of these ensembles at a time most Australian gardens were rose- and dahlia- and gladioli-mad, and relatively few were championing native plants.

Author

Stuart Read is working for the NSW Heritage Office on better planning, maintenance and management of historic gardens and cultural landscapes around NSW. He has a Bachelor of Horticulture and a Post Graduate Diploma in Landscape Architecture. Stuart has worked with the Australian Heritage Commission on natural and cultural heritage, and Environment Australia’s World Heritage & Biodiversity Units. He has a keen interest in identifying and conserving cultural landscapes, cultural layers in natural landscapes, historic parks, trees, views and urban design.

Further reading

Freestone, R and Nicholls, D, ‘Recreation, Conservation & Community: the secret suburban spaces of Walter Burley & Marion Mahony Griffin’, in Bourke, M. and Morris, C (eds), Studies in Australian Garden History. Australian Garden History Society, 2003 pp4–10.

Griffin, W B, ‘The Modern Architect’s Field: its limits and discouragements’, in The Australian Home Builder, November 1922 p.38.

Harrison, Peter, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995.

Miller, W, 1915, The Prairie Spirit in Landscape Gardening (original text),

facsimile reprint, 2002, by the University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst and Boston, with the Library of American Landscape History, 2002.

National Capital Authority (NCA), ‘Griffin’s Federal Capital Design’ in Canberra: the Nation’s Capital, website:www.nationalcapital.gov.au/history/history_05.htm

Price, N, Walter Burley Griffin. Bachelor of Architecture thesis, University of Sydney, 1933 (prepared in consultation with Walter Burley Griffin).

Rubbo, Anna, ‘Through the looking glass of “Magic of America”: Marion Mahony Griffin’s role in the Australian and Indian practices’, in Turnbull, Jeff and Navaretti, Peter Y (eds), The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. Melbourne, Miegunyah Press (Melbourne University Press), 1998, pp38-46.

Vernon, C, ‘An “accidental” Australian: Walter Burley Griffin’s Australian–American landscape art’, in Turnbull, Jeff and Navaretti, Peter Y (eds), The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. Melbourne, Miegunyah Press (Melbourne University Press), 1998, pp2-15.

Vernon, C, ‘The Landscape Art of Walter Burley Griffin’, in Anne Watson (ed) Beyond Architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin: America, Australia, India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998, pp86–103.

Vernon, C, ‘Expressing Natural Conditions with maximum possibility: the Australian Landscape Art of Walter Burley Griffin’, in Journal of Garden History, Garden History Society (UK), vol. 15: 1, Spring 1995, pp19–47.

Vernon, C, ‘Griffin & Australian Flora’, in Australian Garden History, vol. 8: 5, March/April 1997.

Vernon, C, 2002, ‘Introduction’, in Miller, W., op.cit. (facsimile reprint).

Walker, M, ‘The Development at Castlecrag’, in Turnbull, Jeff and Navaretti, Peter Y (eds), The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. Melbourne, Miegunyah Press (Melbourne University Press), 1998. pp74–79.

Walter Burley Griffin Society Inc., The Griffin Legacy: Castlecrag Heritage (brochure pdf 752kb), Sydney, Walter Burley Griffin Society & NSW Heritage Office, 2004.