It has always been difficult to assess the significance of the life and work of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, both in Australian and international terms. Despite all that is recorded about them they remain somehow mysterious figures. Although they have importance in Australian history, and over eighty years have passed since the Canberra competition, there have been no comprehensive biographies. All we have are many articles and books about aspects of their architecture, planning and landscape design. The late Peter Harrison believed that “the complete story of Griffin is never likely to be tracked down.” (Harrison, 1995, p.2)

International reputation

Was Walter Burley Griffin a major talent in the history of American architecture who was half-forgotten and under-rated because he left the USA at age thirty-six? Were he and his wife Marion Mahony true internationalists whose partnership was the most important and original architectural and planning venture ever seen in Australia? Or were they mere derivative followers of Frank Lloyd Wright: minor provincial figures who briefly captured international attention with their beautifully-presented competition-winning plan for Canberra, but whose careers were otherwise undistinguished?

There is growing evidence for the claim that they were highly significant figures whose activities spanned several continents and cultures, who drew knowledgeably upon diverse and powerful intellectual and conceptual sources, tackled some of the biggest jobs then available, and produced distinctive designs and structures which often seem ahead of their time. Yet from another perspective theirs can seem a story of frustration, marginalisation, bad luck, bad timing, and even failure.

Relationship with Frank Lloyd Wright

Direct comparison with Frank Lloyd Wright, often implied but seldom expounded, is sometimes used to relegate the Griffins to the status of minor talents. Contrary to popular perception, they were not dependent on Wright for their style, career start, or original prominence.

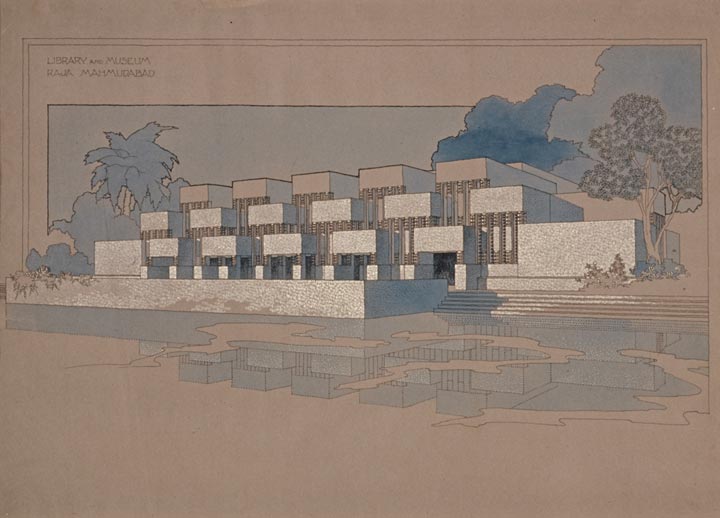

Wright spent almost all his working life in the USA, with more and richer clients, and at a time of US cultural and media dominance of the modern world. Wright had the advantage of living longer than Griffin by some thirty years, which enabled him to produce his best late work, and also to build his own legend. Unfortunately, in order to make a fair comparison we are reduced to speculation; but it is necessary to say that if Walter Griffin had lived a few more years and been able to build some of his spectacular geometric colourful Indian designs, comparison with Wright would do him no harm, and the world history of modern architecture would be different. This is speculation, but it is not nonsensical fantasy: the designs exist and show Griffin moving into a new phase of unprecedented imaginative creativity. James Weirick has spoken of this and other of the Griffins’ best work as pointing to a lost style: “the great decorative modernism that might have been”.

Their association with Wright influenced both Griffins, but they had their own mature styles, both individually and through their remarkable partnership. The impossibility of separating their professional and private lives is reinforced by the fact that their marriage occurred in the year that changed their lives in another respect also: 1911 saw the announcement of the competition for a plan for the proposed but as-yet-unnamed Federal Capital City of Australia. In hindsight, we may feel that life might have been easier for the Griffins if Walter Griffin had accepted the other job offered him that year and returned to the University of Illinois as Professor. It is not surprising that he chose to go to Australia. Few architects in any era have the opportunity to plan and build a major city, let alone a federal capital for an emerging nation with apparently limitless future prospects.

Among the most persistent Griffin myths is the common belief, still occasionally stated in history texts, that the Griffins left Wright’s employ to go to Australia. This is incorrect, as Marion Mahony had left Wright to go to another job in 1909. Walter Griffin had successfully branched out on his own in 1905 at the age of twenty-nine, and his career had been building well. Ironically, it really took off after he won a degree of international fame for the Canberra plan, but by then he was not much longer for America. This is an important point because it refutes the impression Wright later tried to give, that the Griffins were merely a couple of his junior assistants.

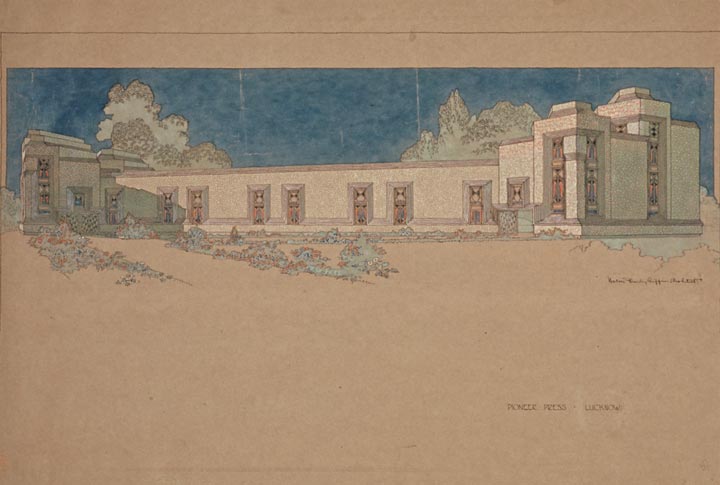

Detail from Pioneer Press Building, Lucknow, perspective drawing by Marion Mahony Griffin, 1936. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Detail from interior view of Capitol Theatre, Melbourne. National Library of Australia, Eric Milton Nicholls collection, PIC/9929/850, Album 1092/5

Canberra in retrospect

Another confusing irony lies in the fact that in Australia, Walter Griffin is best known as the designer of Canberra. Most visitors to Canberra think they are seeing his vision realised. Canberra as it has been built has some important indicative echoes of the Griffin vision, but the vision is grossly diluted and adulterated. In a vain effort to preserve the integrity of their plan, the Griffins fought a long losing battle with the federal authorities. In The architecture of Walter Burley Griffin, Donald Leslie Johnson blames “the bitter years of Canberra” for the decline he sees in the quality of Griffin’s domestic architectural designs, reluctantly suggesting “the burden of the Canberra affairs must have taken a heavy toll on the sensitive man….” (p.97).

In hindsight, it seems that Canberra made and unmade Walter Griffin. At the time of their marriage, the Griffins may have had personal as well as professional reasons for abandoning their American career and coming to Australia. Griffin could have basked in his success, and continued his American practice, or taken the university job. Instead, he and Marion Mahony showed their commitment to their ideals by deciding to try to implement the prize-winning concept. But the unforeseen frustrations of trying to implement the plan cost them dearly. Writing about this crucial turning point in Walter Griffin’s career, Peter Harrison suggested that the stubborn idealist in him meant that: “it is unlikely, even had it been possible to foresee the outcome, that he would have adopted any other course.” (p.3)

Other contributors to this website show beyond doubt that the Griffins produced much outstanding and original architecture, and played an important part in the development of Australian culture in their time, embodying key trends as diverse as spreading American influence and increasing interest in growing Australian native plants. Yet there is also a strong sense of under-achievement. This is most obvious in the regrettable situation that neither Canberra nor Castlecrag developed as the Griffins had intended. They lived in difficult times, and the political and economic disasters of the First World War and then the Great Depression respectively placed insuperable obstacles in the path of these two major projects.

Personal and professional landmarks

The coincidence of personal and professional landmarks continues to the end of the Griffins’ partnership. Encouraged by a substantial commission for Lucknow University library, Walter Griffin went to India in 1935, and it is easy to blame his death after just over a year in that country for the lack of realised projects. It seems another example of the Griffin jinx that the biggest job he actually completed in India, a complete set of stunningly inventive buildings for the United Provinces Exhibition at Lucknow in 1936-37, was always meant to be temporary so was duly demolished. However, several of his Indian projects were abandoned in his lifetime, and others on the drawing board at the time of his death could have proceeded had the clients or authorities wanted to see them built.

Discussion of these questions in Australia often bring forth the accusation, almost part of the Griffin legend, that they were too idealistic and impractical, personally eccentric or difficult to work with. Mahony, in her joint autobiography The magic of America, portrays their lifework as an exhausting struggle against mediocrity and bureaucracy, and announced this in her chapter titles such as “The national battle” and “The municipal battle”. Perhaps Mahony’s strong personality and unconventional views on some matters raised conservative hackles in an era when professional women were rarer than today and females were less often encouraged to be assertive. Similarly, their interest in Theosophy and Anthroposophy, far more common in educated circles in their time than now, can be misconstrued to suggest weirdness. In fact, Walter Griffin’s career, particularly in the USA, provides plenty of counter-evidence that he was adaptable, diplomatic, practical, good at communicating with clients and often able to get his way.

Professional life was possibly made more difficult by the lack of precedents for the kind of professional practice they tried to achieve for many of these years. Only the railways facilitated their efforts to operate between and across Canberra, Melbourne and Sydney at a time when most architectural practices in Australia were locally based. By spreading themselves across several Australian states and cities they compounded the effect of also moving between continents. Although they produced important work in many places, there was no one place where they really belonged and which adopted them, maintained their creations, preserved their documentation, and boosted their reputation.

It is reasonable to suggest, however, that the childlessness of the Griffins’ marriage has been a factor in their confused and ambiguous personal and professional reputation. Children often play a major role in collecting and retaining information and objects relating to their parents, and in shaping their posthumous image. In February 1937, when Walter Griffin died suddenly in India and was buried in an unmarked grave, Marion Mahony was sixty-six. With no family to keep her in Australia, she returned to the USA. In her late writings, and her handling and disposition of the drawings, documents and few other items she retained from her partnership with Walter, she tried to record and preserve her version of their life and work, but it was not to good effect. Old, ill, lonely, poor and disillusioned, she became increasingly dotty while living in retirement with a niece until 1961 when she died aged ninety. This proud, creative, history-making professional woman, born in the apocalyptic year of the great Chicago fire, was buried a pauper.

The childlessness factor is compounded by a lack of professional continuity. With Mahony gone, the Griffins’ partner Eric Nicholls worked on for many years, and Griffinesque echoes can be seen in some of his own designs. Eric Nicholls and later his children Marie and Glynn remained loyal to the Griffins’ memory and conscientiously preserved many of their drawings, pieces of furniture and personal items including books. But no firm survived bearing the Griffin name.

Recognition

Today, the Griffins are recognised and respected by architectural historians and fortunate property owners in the USA, and celebrated in several parts of Australia, specifically Canberra and Castlecrag, though ironically in both the latter places their vision has been at times ruthlessly compromised.

The Griffins attracted and inspired extensive press and magazine coverage, and wrote their share of articles and speeches, but less ephemeral, more extended study of their work was late in appearing. James Birrell’s 1964 Walter Burley Griffin suffers from lack of information. An expatriate American resident in Australia, Donald Leslie Johnson, published The architecture of Walter Burley Griffin in 1977, followed by the first thorough Griffin bibliography in 1980. Peter Harrison’s master’s degree thesis on the landscape architecture was written at the same time as Johnson’s text, and was frequently revised by its author who died in 1990, but it did not appear in book form until 1995. By then, public and media interest in the Griffins was the highest it had been since their lifetime, and the publication trickle was looking like a regular flow, with two titles in 1994: Walker, Kabos and Weirick’s Building for nature; Walter Burley Griffin and Castlecrag, and Peter Proudfoot’s provocative The secret plan of Canberra. Two more substantive works appeared in 1998, the Powerhouse Museum’s Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia and India edited by Anne Watson, and Jeff Turnbull and Peter Navaretti’s The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin.

In the USA Mati Maldre and Paul Kruty’s Walter Burley Griffin in America was published in 1997 proclaiming that Walter Burley Griffin deserved the same exaltation as Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. A year later Kruty and Sprague’s Two American architects in India: Walter B Griffin and Marion M Griffin 1935-1937 detailed the extraordinarily creative final year and a bit of Walter Griffin’s life.

Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin were important members of the so-called ‘Prairie School’ of Chicago, and arguably the most important international architects ever to work in Australia. We are left with the question of whether professional artistic and architectural reputations were or are generally national, or can be truly international? At first glance it seems odd to suggest that movement between countries could prevent rather than facilitate international recognition. Yet this can happen, because so-called ‘international’ recognition is often really just an extension of recognition in a single powerful centre or nation, which exerts cultural hegemony by presenting its own values and developments as universal. Overall, the evidence suggests that the Griffins’ international relocations limited rather than enhanced their opportunities, achievements and recognition.

Author

Dr David Dolan, Professor of Cultural Heritage at Curtin University, was previously Manager of Collection Development and Research at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, and before that was Fine Arts Adviser in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Canberra). He is the author of numerous reports, conservation plans and interpretation strategies; a Member of the Heritage Council of WA 1996-2001 and again since 2005; a Councillor of the National Trust (WA) since 1995 and its Chairman since 2001. David has been an invited and keynote speaker at history, heritage and museum conferences in Australia, England, Germany, Hong Kong, New Zealand, and the USA, also publishing in professional journals in several of those countries plus Canada.

Further reading

Harrison, Peter, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995

Johnson, Donald Leslie, The architecture of Walter Burley Griffin. Melbourne, Macmillan, 1977

Kruty, Paul and Sprague, Paul E, Two American Architects in India: Walter B. Griffin and Marion M. Griffin 1935–1937. Urbana-Champaign, School of Architecture, University of Illinois, 1997

Maldre, Mati and Kruty, Paul, Walter Burley Griffin in America, Urbana and Chicago,University of Illinois Press, 1996

Turnbull, Jeff and Navaretti, Peter Y (eds), The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. Melbourne, Miegunyah Press (Melbourne University Press), 1998

Van Zanten, David T (ed), Walter Burley Griffin: Selected Designs, Illinois, Prairie School Press, 1970.

Watson, Anne (ed), Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia and India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998

Walker, M, Kabos, A, and Weirick, J, Building for nature; Walter Burley Griffin and Castlecrag. Sydney, Walter Burley Griffin Society, 1994

Wood, Debora (ed), Marion Mahony Griffin: Drawing the Form of Nature. Illinois, Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University Press, 2005.