‘The immediate source of inspiration for the Griffins was Louis Sullivan and his over-arching conception of democracy as the highest form of emancipation in all spheres of life.’ (Professor James Weirick, Beyond architecture, p.63)

‘By the time the Castlecrag project was launched, the Griffins had discarded exotic notions of landscape embellishments and had developed such a reverence for the natural Australian landscape that its preservation was adopted as a dominant theme in their ideas for the community environment.’ (Peter Harrison, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect, p.76)

‘Their shared philosophical ideals and spiritual beliefs, combined with their unshakeable faith in the capacity of architecture, landscape architecture and community planning as a force for realising these ideals, provide a framework for understanding their complementary roles in the making of architecture.” (Anna Rubbo, The Griffins in Australia and India, p. 46)

The philosophical foundations to the urban planning and architectural design work of Marion Lucy Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin have been subject to varying interpretations by scholars. This section provides an overview of the current assessment of these foundations. It follows the progression of the Griffins’ spiritual journey from its roots in Chicago, through a period of high social and political idealism during the early stages of the Canberra project, to the anthroposophy and ‘occult science’ that they embraced in their latter years.

Philosophical roots

The beliefs that shaped the early lives of Marion Mahony and Walter Griffin were dominated by the liberal ideals of transcendentalism – based on the 1830s teachings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Effery Channing, Theodore Parker and others – and the independent protestant churches in Chicago of which they were members (Weirick, 1998, p.59). It was a belief system in which the source of religious authority was to be found within the individual.

Marion Mahony was an active member of the Church of All Souls at Evanston, Chicago. Its pastor, James Vila Blake, based his preaching on a commitment to ‘Natural Religion [that] does away with the pretence of divine authority. The religious nature is not created by any institution, now depends on a form, nor is it bound to a doctrine.’ Blake believed that ‘after a time, a new prophet is needed and arises to bring forth religion once more into the simplicity of the spirit and the authority of our soul.’ (Weirick, 1998, pp59-60)

In 1902 Marion was commissioned to design the first permanent place of worship for the Church of All Souls. It was her first independent work as an architect and the only building she ever published under her own name. The small stone chapel (demolished in 1961) has simplicity, strength and inner depth that is in harmony with the congregation’s Covenant of Faith (Weirick, 1998, p.61). The chancel features leaded stained-glass skylights and a mural painted by Marion.

Walter Griffin shared a similar experience of liberal Protestantism through the Congregational Church in Chicago. When the family moved to the suburb of Elmhurst on the western fringe of the metropolis in 1893, they joined Christ Church, which was organised on non-denominational lines. Its doctrine was more fundamentalist than that of the Church of All Souls, but it had an active social outreach program to the ‘poor, the afflicted and the stranger’.

The second philosophical influence on Marion Mahony and Walter Griffin was the American ‘civil religion’ of freedom and democracy, based on the writings of Walt Whitman and Thomas Jefferson. Their immediate inspiration was Louis Sullivan, whose saw democracy as the highest form of emancipation of life. Walter was in the audience for Sullivan’s celebrated address ‘To the Young Men in Architecture’ in June 1900 and the influence of Sullivan’s edict that ‘Form follows function’ is evident in Griffin’s work and writings.

Both Marion Mahony and Walter Griffin were imbued with an enthusiastic appreciation of nature. Mahony grew up in Hubbard Woods, a far northern suburb of Chicago. As a young girl she would venture into the forested ravines and woodland dells that extended down to Lake Michigan. Walter Griffin grew up in the western ‘prairie’ suburbs of Chicago with their open grasslands dissected by tree-lined streams.

For both Mahony and Griffin ’nature was to be their great source of inspiration’. They combined this with ‘a search for pure form – a geometric, abstract ideal – inspired by the patterns of Nature. This love of nature was evident not only in their work, but also in their lives. They both became passionately involved with early conservation groups in the Midwest. This environmental idealism formed the basis of Griffin’s practice in landscape architecture. In Chicago, he designed subdivisions which shared open space in the form of internal parks which was radical at the time.’ (James Weirick, WBG Society News Update Oct. 97)

Response to the Australian landscape

Walter Griffin came to Australia as a world-renown planner and architect who had conceived a ‘city not like any other city in the world, not just a new city for a new nation – a democratic city for a democratic nation.’ (Weirick 1998, p.63) Seven years later he left the project, a disillusioned man who had been thwarted at every turn. The Griffins’ idealised vision of Australia had been totally destroyed and it was evident that their American ‘civil religion’ of democracy and freedom had not taken roots in their new society.

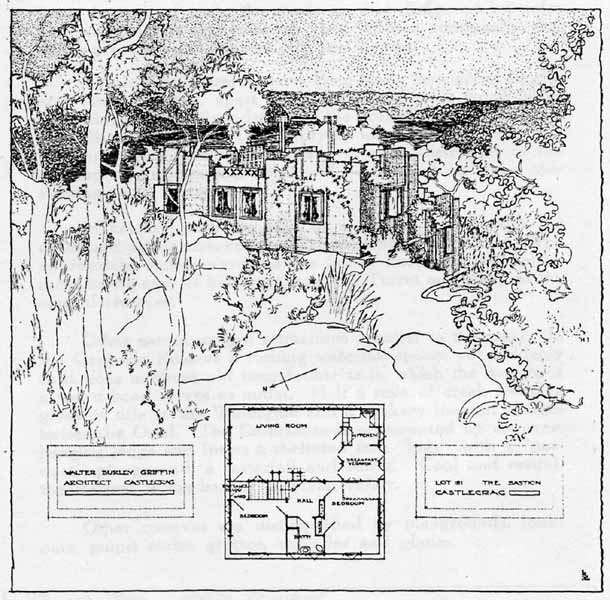

Nevertheless, the Griffins were beginning to develop a successful commercial practice in Melbourne and they established a supportive network of friends there. It was their project at Castlecrag, however, that was to reunite the Griffins’ vision for an idealised urban community and they moved there in early 1925 to implement their dream.

Given their appreciation of nature gained in their formative Chicago years, both Walter Griffin and Marion Mahony transferred this interest to the characteristics of the native vegetation in their new environment, particularly the Australian bushland. Their enthusiasm for indigenous trees and shrubs was far ahead of its time. The Griffins acquired a good knowledge of the nature and habits of Australian flora and Marion produced a portfolio of beautiful colour-rendered drawings of local trees on satin. As Peter Harrison notes, by the time they moved to Castlecrag, the Griffins had developed a reverence for the natural Australian landscape and its preservation was a dominant theme in their ideas for the community environment (p.76). This legacy at Castlecrag continues to guide the local community.

Anthroposophy

From mid-1926 the Griffins came into contact with members of the Theosophical Society in Sydney. Founded in New York by Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in 1875, the Society had established its international headquarters in India in the 1880s. Its activities in Australia were expanded with the arrival of George Sydney Arundel as General Secretary in 1926. The Griffins’ contact with the Society through the Dutch philosopher and Sydney resident Dr JJ van der Leeuw, who made a significant endorsement of the Griffins’ work and brought several clients to their practice. Walter Griffin made an address to the 1928 annual convention of Sydney theosophists and published several articles in its journals, including ‘Building for nature’ (Advance Australia, 1928, and ‘Architecture and the economic impasse’, The Theosophist, 1932). While theosophy had some affinity with the Griffins’ philosophical beliefs, it differed significantly from their long-held principles in its central tenets. By the 1920s the leading figures in the international theosophical movement, Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater, had become committed to an Adventist expectation of a new World Teacher, a vision of a coming Christ (Weirick, 1998, p.80). Their belief sought to re-establish the authority of the church from without, not from within. It was not for the Griffins.

They turned instead to Rudolf Steiner and anthroposophy. This belief system, which Steiner described as a ‘path of Knowledge, to guide the Spiritual in the human being to the Spiritual in the universe,’ originated as an independent current of thought within the German Section of the Theosophy Society. Essentially a form of Christian theosophy, anthroposophy recognises Christ as the one great spiritual teacher. To the Griffins, Steiner’s version of occultism to ‘gain knowledge of higher worlds’ provided a way to ‘revitalise their creativity and energy, to recharge the “authority from within” which was the essence of their life philosophy – and raise it to new realms.’ (Weirick, 1998, p.81)

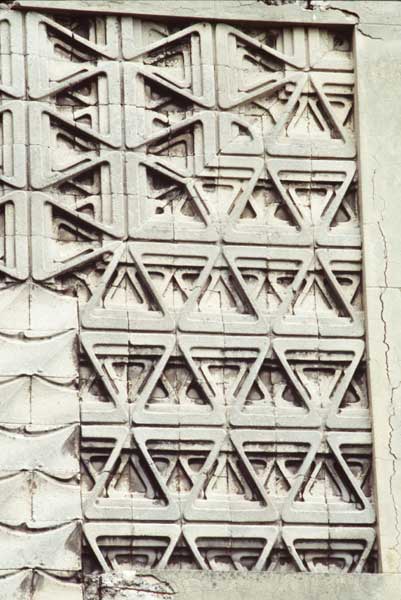

In his principal writings after 1930, Griffin always acknowledged his debt to Steiner, but this is not immediately apparent in his architecture. The symbolic content of his buildings comes from the influence of the American transcendentalists and Louis Sullivan, together with his personal exploration of the Australian bushland. When Griffin was invited to address the Australian Institute of Architects in December 1930, he drew on the Hindu writer, Kahlil Gibran to explain his Castlecrag houses:

‘Build of your imaginings a bower on the wilderness ere you build a house within the city walls. And tell me … what have you in these houses? … Have you peace, the quiet urge that reveals your power? … Have you beauty, that leads the heart from things fashioned of wood and stone to the holy mountain? … Or have you only comfort, and the lust for comfort, that stealthy thing that enters the house of a guest, and then becomes a host, and then a master?’ (Harrison, 1995, p.83)

Griffin’s audience was not receptive to his core themes. To them, the Castlecrag houses that submerged the works of man in untamed bush was a denial of architecture and the retention of the natural rocks and shrubs was the antithesis of landscape design. It would take another generation before these principles were finally understood and embraced.

Mahony embraced anthroposophy more fully than Griffin and her romantic imagination eventually carried her beyond its precepts into highly personal forms of mysticism (Harrison, p.83). Following her return to the United States in 1938, she began writing her unpublished magnum opus, ‘The magic of America’, which tells of her role in the partnership with Walter, both as ‘a forceful intellectual and spiritual muse to a more retiring, yet equally strong minded Walter’ and as the practical organiser of the office (Rubbo, The Griffins in Australia and India, 1998, p.39). The work shows that Mahony lived a feminist principle well ahead of her time in the way she was able to integrate the various aspects of her life into a whole, but it also contains much ‘quasi proselytising religiosity’ that makes it ‘a contentious document in the eyes of many Griffin scholars.’ (Rubbo, Beyond architecture, 1998, p.46)

Author

James Weirick is Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. He has written and lectured extensively on diverse aspects of the Griffins’ works and lives. His interest in the Griffins, which extends over thirty years, was initiated through his uncle, Colin C Day, who worked as Walter Burley Griffin’s last articled pupil and who lived with the Griffins at Castlecrag in the 1930s.

Further reading

Harrison, Peter, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995

Rubbo, Anna, ‘Marion Mahony: a larger than life presence’, in Anne Watson (ed), Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia, India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998, pp40–55

Rubbo, Anna, ‘Through the looking glass of ‘Magic of America’: Marion Mahony Griffin’s role in the Australian and Indian practices’, in Turnbull, Jeff and Navaretti, Peter Y (eds), The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. Melbourne, Miegunyah Press (Melbourne University Press), 1998, pp38-47

Weirick, James, ‘Spirituality and symbolism in the work of the Griffins’, in Anne Watson (ed), Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia, India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998, pp56–85