Early influences

Walter Burley Griffin’s professional career in architecture had a most fortunate start. In 1899, as a 22 year old straight out of the University of Illinois, he started work in the celebrated Steinway Hall, the birthplace of the Prairie School of architects some three years previously. Here he formed a relationship with Frank Lloyd Wright, which would last, off and on, for 10 years. Before leaving for Canberra in 1914 he had established a distinctive style of his own, generated a reputation as a dependable, highly professional architect, built a large and successful practice and completed more than 130 designs, about half of which were built.

In 1894 as only the second woman to graduate in architecture from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the first registered woman architect in Illinois, Marion Lucy Mahony also began her career in Steinway Hall. After working there for a short while with her cousin Dwight Perkins, she had begun to work for Frank Lloyd Wright in 1895 and went on to become effectively the head designer of Wright’s office (Anna Rubbo, Beyond Architecture essay ‘Marion Mahony: A larger than life presence’) and the longest-standing member of his office.

Early commissions

In 1900, while still learning his trade, Walter Burley Griffin attended a talk by Louis Sullivan that profoundly influenced his career. “It unleashed in Griffin a passionate resolve to create his own kind of modern architecture, not based on past styles but, like Sullivan’s work, made from the elements of abstract form itself.” (Kruty, p.17). Soon afterwards he followed Wright to the Oak Park studio where, by 1903, Griffin was handling design commissions for his own clients, with Wright’s agreement. It was here that he met Marion Mahony who came to play a leading role in preparing the studio’s magnificent presentation drawings, and the design of furnishings, decorations and craft objects. The exact status of Griffin at the Oak Park studio remains a matter of some doubt. Most scholars agree that Wright was the master and exerted the greater influence on the younger colleague, but Griffin clearly “provided a stimulation which few others could have done.” (Harrison, p.19).

Independence from Wright

Walter Griffin returned to Steinway Hall in 1906 to strike out on his own. After a slow start he received a commission from Harry Peters (a property developer, as were many of Griffin’s American clients) and designed a house which was ground-breaking in many respects, particularly its use of an L-shape or ‘open-plan’ living area around a central fireplace. This was to become the ‘trademark’ of Prairie School houses and, subsequently, widely adopted in twentieth century residential design worldwide. By 1908 the practice had become more lively and, in the following three years, upwards of a dozen houses, a club house and a library were commissioned.

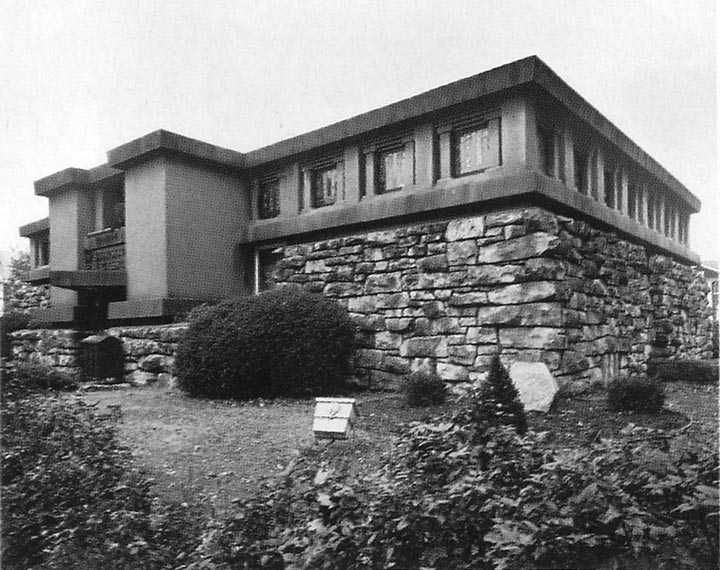

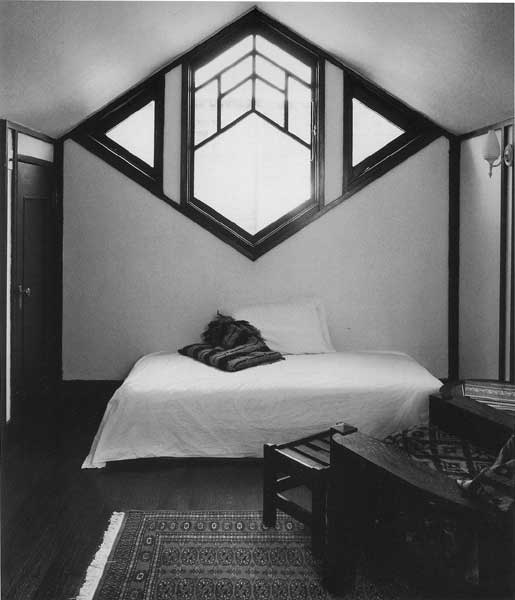

Griffin’s style progressively moved away from Wright’s and that of other Prairie School architects so that by 1910 his work was distinctive. His designs emphasised strong massing, and a subtle balance between formal and informal components. He also began to use new materials and technology: the ‘Solid Rock’ house was amongst the first private houses with a flat, reinforced concrete roof.

After Wright’s ignominious departure for Europe, Griffin once again became associated with Steinway Hall and with Marion Mahony. After their marriage in 1911, Walter and Marion forged the team approach that suited them so well. He was dependable, reflective, highly inventive, precociously skilled architecturally and technically adventurous. She was outspoken, creative, mercurial and a superb artist. They began to work on designs for suburban developments, some quite large.

Success

In 1911 Griffin finally had the opportunity to realise his ambitions to combine his interests in the bold use of stone and the pre-Columbian buildings of the Mayan civilisation of Central America. This was in Mason City, Iowa, where some of Wright’s clients owned an 18-acre site straddling a ravine, a tract that had remained neglected because of its rugged topography and made conventional sub-division impracticable. The Rock Crest/Rock Glen commission was awarded directly to Griffin due to Wright’s incapacity to fulfil his brief. The 19 houses include designs by a number of Prairie School architects, but it was Griffin’s design for buildings, connecting roads and driveways carefully arranged to preserve and respect the inherent qualities of the site that are most significant. Griffin designed the Melson and Blythe houses, built for the sponsors of the project. These are regarded as high points of American domestic architecture, with the Melson House being described as: “one of the irreplaceable houses of the twentieth century … A fantasy in rough stone on the brink of what had once been the town ash heap … this showed a command of stone which Wright was not to equal for many years.” (Harrison, p.23).

The Rock Crest-Rock Glen project survives as the “nearest approach to a complete demonstration of Griffin’s talents for the design of a total domestic environment. The combination of architecture and landscape as complementary disciplines directed towards the creation of a coherent scheme for community living was a significant landmark in his career.” (Harriso, p.22).

Marion Mahony also had many commissions including that of the David Amberg house in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the Adolph Mueller house Decatur, Illinois, and a large residence for Henry Ford in Detroit which was not built.

The Griffins were enjoying remarkable success both professionally and commercially when the news of his Canberra success arrived. In 1913 The Western Architect devoted an edition of its newsletter entirely to his work. With some 10 people on his staff he had recently outgrown Steinway Hall and moved his practice. Suddenly he was famous. Enquiries about possible commissions, some highly prestigious, rolled in. He was later invited to set up a chair of architecture at the University of Illinois which, because of the apparent challenge and status of the Canberra commission, he declined.

To Australia

In mid 1913 he visited Australia and soon returned to the USA to prepare to leave for his Canberra commission. He had persuaded the Federal authorities that, as well as continuing to have his overall design responsibilities, he should direct the city’s construction. Such a role obviously would keep him away from Chicago but he believed his practice could be maintained under the management of Barry Byrne, another Wright associate. After a series of misadventures, trust between the two was rapidly eroding and, with the Canberra adventure turning sour, by 1916 Griffin had abandoned hope of maintaining a foothold in the USA. Soon the Prairie School faded and, along with it, Griffin’s fame amongst American architects.

Kruty says: ”Griffin’s upbringing, training, ideals, and talent combined to produce an artist second only to Frank Lloyd Wright among [the Prairie School]…The remarkable body of work produced during those fifteen years in Chicago…forms an important if neglected chapter in the history of American architecture.” (Kruty, p.15).

Author

Andrew Kirk became interested in the Prairie School during the four years he lived in Chicago. Soon after his return to Australia he became a Griffin home-owner. A member of the Walter Burley Griffin Society since the mid 1990s, he served on its committee for some five years including two years as Treasurer, then President from 2002 to 2004. He was a guest at the 2003 Annual Meeting of the Walter Burley Griffin Society of America in Mason City Iowa where he delivered an address on some of Griffin’s Australian work.

Further reading

Harrison, Peter, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia 1995.

Kruty, Paul, ‘Chicago 1900: the Griffins come of age ‘, in Anne Watson (ed), Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia, India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998 pp10–25.

Maldre, Mati and Kruty, Paul, Walter Burley Griffin in America. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Rubbo, Anna, ‘Marion Mahony: a larger than life presence’, in Anne Watson (ed), Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin inAmerica, Australia, India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998 pp40–55.