Overview

Urban planning in Australia has largely reflected international trends, but with some uniquely Australian features. Early Australian settlements were commodity driven, relatively affluent and urban. Historically land was cheap, transport accessible and demand for private, suburban dwellings high. Today the primary difference between Australian cities and those of other nations is their sprawling character and low density. Australia continues to this day to be one of the most highly urbanised countries in the world (Forster 2004, pp.2–13).

Unlike major cities in other countries, many Australian cities were planned. But all cities are also impacted by immigration, economics, culture, transport, health, education and other influences. Urban form and character are also about design, the juxtaposition of historic and contemporary influences, innovation and prevailing form.

As the Australian urban form began to evolve, the United Kingdom was responding to the urban squalor that followed rapid industrialisation. Ebenezer Howard designed Letchworth in the late 1800s, a revolutionary city of concentric circles designed around a central green. In the United States revivalism was being replaced by Louis Sullivan and ‘form following function’.

By the turn of the century a new informality and newfound respect had emerged for the natural environment, natural materials and textures. New architectural and city designs emerged in Europe and America. The Australian vernacular was also being challenged by local and imported designers. Griffin and his Prairie School contemporaries were drivers of this shift.

The Griffin plan for Canberra

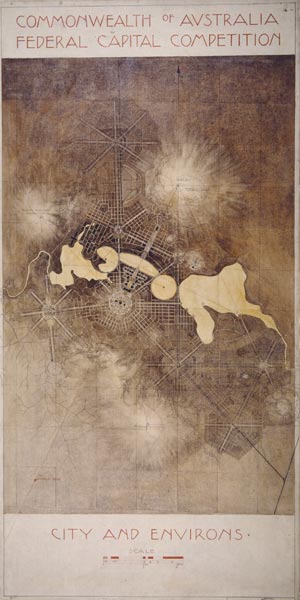

The competition for the design of Canberra, Australia’s capital city, provided an opportunity for entrants, including Griffin, to conceive a whole new city based on these emerging concepts by exploring the relationship between built and natural form and city function. Walter and Marion Mahony Griffin laid out the city to take advantage of the beauty of the natural landscape. They applied the natural advantages of the locality to the civic necessities of a national capital city (Forster, 2004, pp2–13).

Griffin predicted the need for urban planning to be flexible to meet the demands of growth and changing needs over time. Griffin said that:

‘Any arrangement looking forward one hundred years has to be elastic, permitting street improvements and construction to proceed little by little, no faster than the city growth demands, but at the same time in a way that will be adequate ultimately without the constant shifting of site uses in the various sections, which has led to terrific waste through destruction of property in all our cities heretofore.’ (Birrell, 1964, p.75)

Griffin designed a city at the cutting edge of urban planning. It incorporated axes terminating at the foot of dominant natural features — peaks and hills — or built points of importance. He created distinct functional domains. Gardens and natural landscapes flanked or provided backdrops for important buildings or precincts. From geographic high points he created long, sweeping vistas framed by native vegetation.

The strong geometry of Griffins plan was tempered by waterways and curved forms. Groups of buildings faced one another across the water, softening and separating recreational and administrative zones, the civic centre and the capital.

Griffin delineated and provided for suburbs without designating outlying centres or future suburbs considering that these would need to be flexibly determined to meet the needs of the expanding population. Suburbs were green and common parks and gardens abundant. Transport was integrated and business and industry were clustered on the fringe. Government functions were centrally featured as in L’Enfant’s design for Washington.

Griffin designed intuitively and many of his ideas predated broad adoption. While some elements of his design were never realised, the primary vistas are strongly reminiscent of the beautiful renditions of the garden city as captured in the enduring city competition artworks of Marion Mahony.

Griffins plan continues to provide the backbone and compositional canvas for urban planning and design in Canberra. A revival of interest in the Griffin legacy coincides with new urbanism, city revitalization and a desire to preserve the core character of our cities globally, while addressing the challenges of increasing density, congestion, sustainable resource management and global competition.

Other Griffin urban designs

But Canberra was not the beginning, nor the end, of Griffin’s urban planning. Mossmain at Montana in the USA (not built) followed, as did Griffith and Leeton in NSW, both partially built. The suburban design for the irrigation towns of Griffith and Leeton was reflective of the Canberra concepts — a central circular park surrounded by an octagon of streets radiating from the town centre with nearby green spaces.

Griffin’s own suburbs of Castlecrag in Sydney, and Eaglemont in Melbourne also reflect loop circulation systems, transport routes following natural contours, and open common areas providing for enjoyment of surrounding vistas. These remain to remind us today of the newness of these concepts and, together with the remaining buildings designed by Griffin and his cohorts, provide us with fine examples and an opportunity to appreciate the Griffin/Mahony vision.

Griffin developed other urban designs for Jervis Bay, Ranelagh, Milleara, St Kilda, East Keilor and Newcastle, to mention just some of the schemes on which he and Mahony worked while in Australia. On a lesser scale Griffin developed masterplans for the University of NSW, University of Sydney and the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque USA (Birrell, 1964 p.75).

Although few of Griffin’s urban designs were realised, they demonstrate his broad vision and passion for design and urbanism well beyond architecture.

Author

Di Jay is Chief Executive Officer of the Planning Institute of Australia (PIA), the national professional body representing urban and regional planners, social planners, urban designers and environmental planners. Di has a background in public policy, corporate governance and public affairs. She represents PIA on the boards of the Building Design Professionals, the Australian Construction Industry Forum and the Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council. Di is Chair of the Canberra Chapter of the Walter Burley Griffin Society Inc. 2004–2006.

Further reading

Birrell, James, Walter Burley Griffin. Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, 1964.

Forster, Clive, Australian cities: continuity and change. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004 (3rd edition).

Hall, Peter, Cities of tomorrow. Oxford, Blackwell, 2002.

Johnson, Donald Leslie, The architecture of Walter Burley Griffin. Melbourne, Macmillan, 1977.

Mackenzie, Stuart, Wood-Bradley, Ian et al, The Griffin legacy: Canberra the nation’s Capital in the 21st Century. Canberra, National Capital Authority, 2004.